CASH. GRAB. Kong's initial place in history might as well have ended following his first theatrical outing, on a high note, because the somewhat sour aftermath of its success seems to have been largely forgotten by the masses. It is the nature of most successful films that their studio will attempt to milk as much out of it before it's dry. This mentality was very much the driving force behind RKO Studio's follow up to their extraordinary hit, King Kong. King Kong was the first film that gave the studio a real profit, and as such, they were eager to pack people in theaters as soon as possible for more giant-ape mayhem. But that eagerness actually may have been extremely misplaced. Gathering the old gang back together, Merian C. Cooper returned as the executive producer with Ernest B. Schoedsack returning to co produce and direct. Also returning was Schoedsack's wife, Ruth Rose, to write the screenplay. However, production famously went a bit off track when Cooper was outraged to discover that RKO was only allotting them half of the budget that the original King Kong had been given. Not only that, but Son of Kong was set to be released in December of 1933 - within one year of the original's release. This rushed time frame and smaller budget would end up showing in the less-spectacular sets, in the clunky dialogue, the unbalanced story, and it surprisingly even shows in the animation - though, the woes with animation go a bit deeper than mere shallow pockets and crunched time.

|

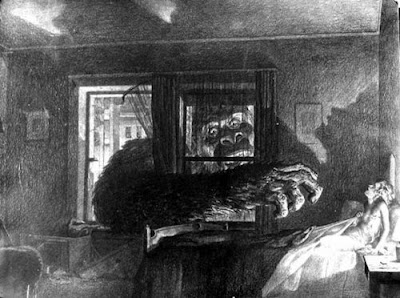

| Perhaps the most famous shot of Willis O'Brien at work - and the most tragic |

Once again Willis O'Brien was put in charge of the animation, King Kong being his first big success since The Lost World nearly a whole decade prior. O'Brien's career had been a rather spotty one up until that point. While The Lost World and King Kong were both incredible achievements, and still endure to this day, there were a whole lot of other projects which did not go so well. Many if not most of the projects he had started were abruptly canceled. And if the spotty career wasn't enough, he had contracted several serious illnesses, and had been involved with an extremely uneasy marriage which ended rather quickly - but not before he and his ex-wife had two sons together. One of the most widely circulated photos of O'Brien (seen above) is of him on the set of Son of Kong, standing next to a model of a styracosaurus. In the photo, he is noticeably disgruntled looking. He seems upset and distant - maybe even hollow. And that is probably because he was. During the production of Peter Jackson's 2005 King Kong, the film's website, KongIsKing.net, provided an article about the production of Son of Kong, as well as what exactly O'Brien must have been thinking about at the time that this picture was taken.

"The subject of the enigmatic photo is Willis O'Brien, and properly describing the importance of this man in making King Kong would take much more space than I'm allotted here, suffice to say that "OBie" arguably represented the heart and soul of the titular character himself. In animating Kong, OBie conveyed a richness of character that almost certainly derived from his own background. After seeing Kong's battles with the T-rex and elasmosaurous, can there be any doubt that OBie was once a boxer? Watch Kong's nuanced final seconds atop the Empire State Building with the following in mind: all OBie had to go on for that scene was this rather succinct scripted action, "He staggers, turns slowly, and topples off roof." There are those who make the case - rather convincingly - that Willis O'Brien deserved a King Kong co-creator credit along with Merian C. Cooper. OBie's conceptual drawings and work on Creation, the project Cooper cancelled in favor of Kong, almost certainly informed Cooper's vision of his "giant ape film" and inspired now-classic sequences. Furthermore, most of the visual lynchpins of the production - miniatures combined with humans, stop-motion animation of giant creatures, jungle vistas with astounding depth, incredible attention to detail - are the province of O'Brien and his staff. Yet for all of his technical wizardry, Willis O'Brien seemed destined to be overshadowed by stronger personalities (in the case of Merian Cooper), opportunistic producers (his King Kong vs Frankenstein concept would be sent overseas courtesy of producer John Beck, who sold it as King Kong vs Godzilla without telling or compensating O'Brien), and broken promises (he had more projects fall apart than you can count on both hands). Which brings us back to the picture. Willis O'Brien's first marriage was characteristically impulsive. Hazel Ruth Collette was twelve years younger than Willis when he began dating her, and, through some manipulation by the girl's aunt, he found himself fairly trapped into an engagement. The marriage seemed doomed from the beginning; OBie felt snared, and, particularly when The Lost World created some financial success and leverage for him, he rebelled with the cad troika: booze, the racetrack, and other women. For her part, Hazel exhibited some markedly unbalanced behavior before and after Willis's indiscretions that, in hindsight, should have served as fair warning of heartache to come. The uneasy union produced two sons, William and Willis, Jr. By 1930, the couple was effectively separated, though Willis continued to take his beloved boys on various outings. Around 1931, the already troubled Hazel contracted both tuberculosis and cancer, and existed in a near-constant narcotic haze. The elder son, William, developed tuberculosis in one eye and then the other, resulting in complete blindness. The boys remained with their mother, and OBie continued to take them to events like football games, where the younger Willis would do descriptive play-by-play for his older brother. By Fall of 1933, King Kong had been released for some time and was undeniably a smash hit. OBie, rightfully proud of his achievement, was now charged with capitalizing on Kong's success with a hurriedly prepared sequel. The much smaller budget for Son of Kong- less than half of its predecessor's cost - meant that its chief technician, Willis O'Brien, the genius who brought the world of Kong to unforgettable life, would continue to make the same $300 a week he'd been paid before. To make matters worse, while O'Brien was left largely to his own devices while creating Kong, producers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack were now familiar enough with some of the processes O'Brien employed that they felt comfortable "making suggestions." When enormous debates arose over matters that would formerly have been resolved simply and autonomously, O'Brien withdrew into a shell and effectively distanced himself from the production. Obie's assistant Buzz Gibson is consequently responsible for most of the animation in Son of Kong. In early October, during the difficult sequel production, O'Brien brought his sons to visit the set, allowing sightless William to handle the delicate miniatures. It was undoubtedly quite a day for the boys and a tension reliever for their father. Later that same week, a neighbor was shocked to hear shots ring out from the home of Hazel O'Brien. When the police arrived they found a nightmare: Hazel lay fully conscious on the service porch floor, a gunshot wound to her chest. Next to her was a .38 revolver with five spent cartridges. William, 14 years-old, lay dead in his bed with two bullets in his chest; 13 year-old Willis, Jr. was found nearby with the same wounds, clinging to life. He would die on the way to the hospital. Mentally unbalanced and despondent, Hazel had shot her two sons and then herself. O'Brien was devastated. In a cruel twist of fate, Hazel's self-inflicted bullet had not only failed to kill her, but actually drained her tubercular lung and extended her life. Too ill to prosecute, she remained in the prison ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. Willis O'Brien never visited her."

|

| Concept art for the aforementioned King Kong vs. Frankenstein project |

Shortly thereafter, the picture of O'Brien and the styracosaur was taken (and the styracosaur model is coincidentally now owned by Peter Jackson himself). Needless to say, the animation in Son of Kong turned out extremely shoddy by the standards of the previous film. That's not to say that the entire production was essentially filled with doom and gloom, however. Son of Kong would ultimately take on a much lighter and even more comedic tone than the previous film. Script writer Ruth Rose intentionally made no attempt to make a serious film like the first one, calculating that it could never surpass the first. She stated, "If you can't make it bigger, make it funnier." And this idea was actually fairly well received by some. Returning from the first film would be several characters (all played by the same actors), those being Carl Denham, Captain Englehorn (the captain of the Venture), and Charlie (the Chinese cook from the original film). Robert Armstrong, who played Denham, actually very vocally preferred the second film over the first one, saying that the sequel offered more character development for Carl Denham. And in all reality, for the most part, it does seem that quite a bit of thought was in fact put into the story.

The story picks just a few months after the events of the first film, with Carl Denham being sued for his part in the destructive rampage Kong went on throughout Manhattan. With bills piling up as fast as the lawsuits, Carl goes to Captain Egglehorn, who fears that the lawsuits will soon start coming to him for his part in the whole mess as well. Thinking fast, Carl and Englehorn decide to flee the country and haul freight down in the South Pacific. Quickly throwing together a skeleton crew, they ship off, escaping the jurisdiction of the New York municipal authorities. By dealing with the direct and very real consequences of the previous film's story, Son of Kong shows the level of thinking and care that went into putting it all together. Sadly, it's about at this point when the rushed production schedule starts to bleed through, as the plot goes completely off the rails.

Sailing the East Indies doesn't go so well for the crew, and we actually get the impression that Denham himself might be missing the life of a showman. One night he spots an ad for a "show" in one of the little towns where they are docked, and he, Englehorn, and Charlie all decide to attend. It's a weird circus sideshow sort of affair, featuring trained seals (whose act is never shown), some musical monkeys (whose act is shown, and it's awesome! Seriously, one monkey is playing a stringed instrument and others are drumming and dancing and they all have little outfits on!), and then a girl comes out and sings poorly to some ukelele song. Most of the crowd seems unimpressed, but Denham seems to think the girl has a lot of personality that could be exploited for a show if used and cultivated in a different way.

That night, the girl and her father (who owns the show) get ready for bed. It's weird, because this girl not only shows up out of nowhere (and becomes a main character by the film's end) but her character isn't ever given a real name. She is played by Helen Mack, and when she is introduced to play her ukulele her father refers to her as "Madame Helene," however, in the opening credits her name is "Hilda," a name which is never used throughout the film. Other than her stage-name, nobody calls her anything. Denham, ever the classy man, just calls her "kid" the entire time. Anyway, she goes to bed while her father meets up with the only other white male in the entire town, a gruff European sailor. Hilda (I guess...) doesn't like this sailor, because he just stays up all night with her father drinking. And indeed, that's exactly what they do. But as they do so, Hilda's father strikes a nerve with the sailor when he accuses him of scuttling his own ship in order to get the insurance money for it, which is why he is stuck in this town (Hilda and her dad are stuck here because her father used to be a part of a huge circus which booted them when her father wouldn't stop drinking). The sailor gets angry and bashes a bottle over the old man's head (which kills him eventually) and the altercation leads to the entire circus tent lighting on fire. The sailor runs off in his drunkenness, and ends up just going to another bar.

At the bar he runs into the somber pair of Englehorn and Denham. It is revealed here that not only has Denham met this man before, but that he is in fact the Norwegian sailor who sold Carl the map to Skull Island in the first film, and is named Helstrom. It's a great callback to the original film, fleshing out the world had been created in this franchise. Really, it's a solid idea, complete with a fun scene where Helstrom claims that he deserves some of the profit (from the Kong incident in the first film) since he provided the map. Denham quips back that he can have half of everything he got from bringing Kong to New York, namely, his eleven law suits and pending indictment. Helstrom is taken aback at first, but then asks if Carl ever found "the treasure" while on Skull Island. This is where literally any and all of the good ideas this film had going for it quickly float out the window and into endless oblivion. The audience knows there's no treasure on Skull Island, and you'd think after what happened last time that Denham would never dare go back. But, Denham is desperate, so he and Englehorn agree to head back, with Helstrom joining the crew.

There's also a part somewhere around here where Denham runs into Hilda who is trying to round up her monkeys that escaped in the fire. She's idiotically standing beneath the tree where they are hiding and just calling to them. Carl says, "You'll never catch a monkey that way," to which she snaps "When have you ever caught a monkey?" "You'd be surprised," he responds. It's amusing. Hilda has nothing to lose and wants to head off with Denham. She knows Helstrom killed her dad, but she has to wait for the magistrate to arrive in order to indict him (or... do whatever their legal system does...). But justice can wait, as she thinks Denham is pretty cool and even recognizes the show-biz manner he carries himself with. So, eventually, they all set sail again for Skull Island.

They land on the beach and are immediately attacked by the natives, who recognize the white men and are pissed off. Denham seems baffled about this, but it doesn't really take a genius (or the dialogue which follows explaining to Denham just why they are mad at him) to understand why; but essentially the natives have had to relocate their village after the gates were destroyed in the first film. Again, Denham seems baffled by this, but what can ya do? So the castaways set off to make landfall elsewhere, and when they do, they immediately run into a baby Kong. The baby is refered to as "little Kong" "Kong's son," and just "Baby" for the duration of the film, but the production team always called him "Kiko," which is an abbreviation of the term "King Kong." Stuck up to armpits in quicksand and muttering all sorts of weird noises, Kiko is meant to be cute, rather than fierce.

While making the original King Kong, there were two armatures used for animating the titular character. One, which is referred to as the "long faced" kong, is extremely fierce looking, and was used for the sequences where Kong battles the Tyrannosaurus and when he shakes all of the sailors off of the log bridge (as well as most of the promotional material). The other Kong model was much cuter, and was able to better portray the less animalistic side to the character. That said, the "cuter" model could still look extremely fierce when it needed to (and does). For Kiko, they took the "long faced" Kong model, stripped it of its skin, and put on a new body. Kiko has white fur and is given a permanently goofy and silly demeanor. Nothing fierce or animalistic here. He is meant to be 500% cute, and at one time (a really random time I might ad) even breaks the fourth wall by looking directly into the camera, scratching his head confusedly, and then shrugging in a classic "I don't know!" pose. It's silly beyond all reason. In the final bit of interesting or worthwhile plot, Denham saves the little Kong (and later bandages him) from the quicksand because he has felt forever guilty about what he did to the first one. From then on Kiko follows them around and saves them from all sorts of troubles.

The rest of the film pretty much flashes by so fast that if you stop to blink you're bound to miss what is going on. A whole barrage of completely random creatures appear out of nowhere for no reason whatsoever. A styracosaurus chases Englehorn, Charlie, and Helstrom into a cave, and Hilda and Denham are rescued by Kiko from an attacking giant bear (?!). This fight is actually entertaining for what it is. After Kiko beats it to a pulp (something Denham actually says Hilda deserves at one point in the film) it bites him again, so he picks up a tree and bludgeons it to death. Again, it's pretty entertaining. There's nothing quite like watching a gorilla take a baseball bat to a bear's face.

It really feels like all of these sequences were just half-thought-out concepts from the first film that they cobbled together to put in here. Kiko smashes a temple wall open, revealing an ugly vampire statue. Denham goes inside and finds some treasure - which is really confusing because Helstrom had just made up the treasure story in order to trick them all out to sea and mutiny against them, thus gaining a new ship. A big snake-lizard-monster comes in snarling like a panther and Kiko kills it. Helstrom sees Kiko and flips out, running down to their boat where he is promptly eaten by a random sea serpent. Anyway, these things all happen incredibly quickly and randomly - and then everything begins to literally fall apart.

With no explanation or build-up whatsoever, the plot is suddenly halted as Skull Island begins to crumble and fall into the ocean. No real reason for this is given in the film's final cut. Some shots make it look like a typhoon caused the disaster, while others make it look like an Earthquake of some sort. Maybe there's a volcanic eruption? Who is to say? There is liberally no explanation. None of the characters even seem to wonder or what is going on, or care at all, making one wonder if the film crew making the movie in the first place cared at all by that point either. Supposedly the script/screenplay featured scenes of tribal warfare and a climactic dinosaur stampede during the island's sinking. The stampede was going to utilize the models that had been built for Creation, however these sequences were never filmed due to the films tight budget and shooting schedule. Anyway, the entire island sinks below the waves, except for one hill on which Denham and Kiko are trapped. Englehorn, Charlie, and Hilda are safely aboard their rowboat, but they realize that they might not be able to save Denham in time. Kiko, his foot trapped in a slowly sinking rock, saves Denham one last time by grabbing him and holding him above the water (even as Kiko himself drowns) until the boat can rescue him. Kiko is submerged, and Skull Island is gone. And then, just as soon as they have been marooned, they are rescued by a passing ship (keep in mind, a passing ship in the location of Skull Island, a place so completely and entirely remote that it was believed to be a myth, and never charted on any maps...). And then the film ends. This whole climax literally takes place over the span of only a few minutes. A fellow reviewer once wrote, "The climax, which appears out of nowhere for no reason at all, happens as though writer Ruth Rose were simply looking for a way-- any way-- to end the movie right now. I confess that right then certainly seemed to me like a good time to end the movie-- I had lost all interest a while before, actually-- but to see it ended in a way that bore some kind of connection to the rest of the story would have been appreciated."

Son of Kong presents some interesting ideas to the viewer as to what happened in the aftermath of Kong's rampage, but fans might prefer to ignore its existence in the core story of the original King Kong altogether. I for one am fairly unsure as to what to make of it. It's very unnerving to see one of the best movies followed up by something so entirely lackluster. Another sequel was never made, and Son of Kong more or less fell into obscurity directly after its release. After all, it was released mere months after the original groundbreaking film. The affect of King Kong was still so fresh that it's no wonder Son of Kong never stood out - and the studio took the hint. No more sequels were produced, save for the spiritual successor, Mighty Joe Young in 1949. And in the following near-century since its release, Kong's legacy has lived on triumphantly through a series of reboots and remakes. In the end, it's unfortunate that RKO let their franchise's original run fizzle out so quickly and so disappointingly (especially considering other monster franchises like Toho's Godzilla or Universal's Monsters - Dracula, Frankenstein and the like - lived on for decades before ever needing to take a break). However, though it ended in a flop, the original film's legacy was obviously not tarnished. It's an incredible testament that no matter how many sequels or spinoffs or remakes, the original King Kong is still hailed almost a century later as one of the best and most impressive American films ever made.