During the days of Georges Méliès experimental conquests, film had begun rapidly developing from short footage of trains arriving at stations, to full narratives in an ever expanding sea of genres. In 1903 the men behind Thomas Edison's own film studio had invented the first western in The Great Train Robbery, and film was quickly catching on as one of the premier art forms in the United States of America. Out of this great cinematic awaking came director D. W. Griffith.

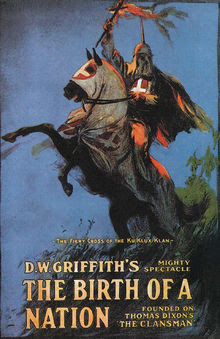

In the interest of full disclosure, I am not a major fan of Griffith's film career. While the likes of Méliès produced what I would consider true cinematic genius, Griffith comes off to me as more of a Michael Bay of the day. Entertaining? Sure. Technically innovative? Without question. Epic? Extremely. But overall, I just find his sensibilities are often in a rather odd place. After spending time as a playwright and trying to get in on Edison Studios - often touted as the first American film studio - Griffith eventually found his own footing when he produced what is often considered the very first "blockbuster" film: 1915's Birth of a Nation. Though it pioneered all sorts of film and narrative techniques that have since become a mainstay of the film industry, Birth of a Nation is notorious for being extremely controversial for its negative depiction of Black Americans, White Unionists, the Reconstruction, and its positive portrayal of slavery and the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan actually serves as some of film's first superheroes, or a sort of twisted Justice League. The film, though popular, was widely criticized and subject to boycotts by the NAACP. Griffith responded to his critics with the mind-blowingly epic Intolerance, intended to show the history of prejudiced thought and behavior. The film was not a financial success but was praised by critics.

|

| A massive set with hundreds of actors from Intolerance |

The first of these films was a decidedly dinosaur-less 1912 film called Man's Genesis. Man's Genesis deals with the story of a weak caveman trying to win the heart of a cave lady, but being generally unable to win her back from the much more masculine and animalistic caveman who already has her. He eventually makes up for his strength by inventing the first club and "becomes a man," winning the lady. Simple and overflowing with Freudian ideas, Griffith decided to follow up on this film two years later with 1914's Brute Force.

In spite of its astoundingly contemporary title, Brute Force is a fairly subdued silent film, with frequent glimmers of cutting edge genius - something that might be said of many of Griffith's films. It runs at about a half hour long, and begins with an inventor (in modern day) named Harry Falkner at a social event. He's excited to see his love, Priscilla Mayhew (who Griffith bothers to characterize in the written text on screen even though she is in the film for only about a minute of time). Priscilla is whisked off and Harry is left feeling rather forlorn and dozes off noting, "Oh For The Good Old Days Of Brute Force And Marriage By Capture!" We are then transported back to the time of cavemen for, essentially, a rehashing of the plot we were treated to with Man's Genesis two years earlier. Only this time it continues. After gaining the club, our little weak hero gets the girl and then becomes leader of his tribe by using it to fend off prehistoric monsters! It's hard to really make sense of among all the grain of the film, - at least, in the print I watched - but there's a serpent-ish thing at first, and then what I think is a turtle with a fin on its back (if anyone out there watches this movie and can tell any better, please do not hesitate to speak up and help identify these relics of monster film history).

However, following the serpent and the fin-turtle, film history is made! Our caveman and woman are having a romantic moment when they are interrupted by a deliciously outlandish beast! I've watched the scene a few times over and can't tell for certain what animal it is, but I believe it's an alligator that the film makers have attached frills, spikes, and plating to in order to make it appear as though it were a dinosaur or some other prehistoric horror. The effect is wonderfully sloppy and silly, and weirdly would set precedent for other films that lacked the budget or time for realistic dinosaur reconstruction prior to the age of CGI. Aptly - and lovingly - this effect is often called the "slurpasaur" effect. Maybe it's my sentimentality for these old monster movies, but I find slurpasaurs completely silly yet still entirely charming. The sound effects attached are also usually a riotous joy, and it's a shame that this film was before the dawn of "The Talkies" because I would love to have heard what noises Griffith felt this thing made. There really is something electrifying to me about seeing this effect being used so early in film history, and so poorly at that. It's honestly hard to tell exactly what they were hoping this creature would look like, because it ends up looking like a totally incomprehensible mess; somewhat akin to a dog running around whilst being trapped under a blanket. Funny, charming, lovable, but a mess.

Fortunately the next creature to appear is much more recognizable - at least in form. After fleeing from the alligator-rug-mess-monster (it turns out to be far too imposing for the protagonists to fight with a club), they run into what is described on-screen as a "peril of prehistoric apartment life." A large therapod dinosaur, which appears to probably be a ceratosaurus, menaces them for a while. Again, the grain on the film makes it a bit hard to see what is going on, but something is dangling from its mouth. Whether that's a tongue, a piece of meat, or whether Griffith envisioned this animal as an omnivore and it's a plant, I'm really not certain. But the cavemen don't put up much of a fight against him, and sort of end up running away from him just like they did with the messy-gator.

No comments:

Post a Comment